A Year in Books For Life

October 16, 2017

I have been working with Heywood Hill, London’s pre-eminent independent bookshop, sourcing rare books for library projects. They have just launched their fantastic Prize Draw to win A Year in Books FOR LIFE.

I cannot enter, frustratingly. But you, dear reader, can – until midnight on 31st October 2017. The first prize winner will receive one newly published and hand-picked hardback book per month – FOR LIFE – delivered anywhere in the world.

I cannot enter, frustratingly. But you, dear reader, can – until midnight on 31st October 2017. The first prize winner will receive one newly published and hand-picked hardback book per month – FOR LIFE – delivered anywhere in the world.

Imagine Elon Musk chooses you for the first manned flight to Mars in 2024. Just answer these two simple questions for your chance to win: what treasured book and what object do you take with you?

Watch the promotional video and find out more about Heywood Hill’s popular ‘A Year in Books’ subscription service

Lives less ordinary, revealed in Leyburn

September 7, 2017

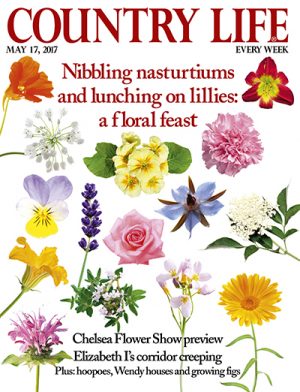

Whilst flicking through a back issue of Country Life recently, I was delighted to chance across Huon Mallalieu’s report on a Book Sale at Tennants Auctioneers of Leyburn.

The 28th April sale, which I catalogued, featured a rare 18th century survey map of Derbyshire by Peter Perez Burdett, and a typescript proof by Sir Genille Cave-Brown-Cave of his memoirs – ‘From Cowboy to Pulpit’ (1926).

Mallalieu sheds further light on these two intriguing personalities and their unconventional lives. Fascinating stories both, well worth a read. The article in full here: Art market, May 17 2017

Canaletto and the image of Venice

June 2, 2017

Canaletto & the Art of Venice at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace (19 May – 12 November) showcases one of the most important collections of 18th century Venetian art in the world. More than 200 paintings, drawings and prints – all from the Royal Collection – explore how Antonio Canaletto (1697 – 1768) and his contemporaries captured the allure of this most evocative of cities.

As much as to any artist, the exhibition serves as testament to Joseph Smith, collector, dealer, artist’s patron-cum-agent, and (when he had time) British consul in Venice from 1744 to 1760. Smith’s collection was bought almost in its entirety by George III in 1762 to furnish the newly purchased Buckingham House (later Buckingham Palace). In fact the paintings now on display were a £10,000 royal afterthought once the bibliophile King George had secured Smith’s magnificent Library.

The Porte Del Dolo c.1740, etching

The artists of this last great cultural flowering of the maritime Republic – before it was swallowed up into Napoleon’s European empire – shared a sense of theatre, and an appreciation of the interplay of light and colour. The son of a leading theatrical scene painter, Canaletto elevated landscape painting while his peers concentrated on their more respectable ‘histories’, allegories and portraits. His market was foreigners, particularly the British – who (encouraged by Consul Smith) snapped up his glistening veduti of canals, palaces, churches and piazzas. Canaletto’s architecture is a glorious backdrop to the regular festivals, masques and ceremonies of the Venetian calendar.

With his nephew Bernardo Bellotto, Canaletto started making etchings in the early 1740s, mostly real and semi-imaginary landscapes inspired by the Venetian mainland. The 31 plates resulting from a journey the two artists made along the Brenta canal were published as a set in 1744 – a kind of prospectus – with an engraved title page dedicated to Smith.

Title plate with a dedication to Joseph Smith 1744, etching

Almost inevitably, these black and white compositions are a little overshadowed by the larger, showy, brightly painted canvasses hanging in the adjacent rooms. After all, the prints were not originally intended for framing and display like pictures, but were bound in an album on Smith’s shelves. Nonetheless the true print lover cannot help but be impressed by the range of light and shade skilfully evoked by varying the space between sinuous etched parallel lines. There is very little of the sometimes rather crude cross-hatching employed by northern printmakers to produce tone.

Final word goes to Canaletto’s large canvasses showing Grand Tourists pottering about the classical ruins of Rome. Each little group has a dedicated guide, identifiable by his sober black attire, pointing out the arches and antiquities half-buried in silt.

The Arch of Septimius Severus 1742, oil on canvas

Painting – and Printing – with Light

August 27, 2016

If you can get along to London’s Tate Britain before the 25th September, I recommend Painting with Light, an exhibition celebrating the links between early photography and art in Victorian and Edwardian Britain.

It cannot be described as a glamorous blockbuster, and the images are generally small and intricate. Not for the faint hearted, it nevertheless repays close attention (and, just, the entry price). The subject is overdue closer scrutiny, as very often painting and photography-as-art are treated in isolation.

Jane Morris (wife of William) posing for artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Doyens of the Pre-Raphaelite, aesthetic and impressionist movements used photographic images as inspiration, as an alternative to the preparatory sketch, or as aid to composition. Photography presented a new, revelatory way of seeing the world, and therefore seeing art. From the 1850s books and journals were illustrated with photographs instead of engravings and lithographs, and the publications of learned Victorian societies were the forums for this conversation.

Many who had trained as artists became photographers, especially portraitists. From the introduction in 1851 of the wet plate process, which produced sepia-tinted positive prints, the number of professional photographers increased from 51 to 2,534 by 1861.

The Lady of Shallot by Henry Peach Robinson, 1861

As technologies for the taking and developing of photographs improved, many artists saw landscape in new ways. The beauty and ‘truth’ of wonderous mother nature – which Romantic artists like Constable and Turner sought to capture – was traditionally deemed to lie in the accurate rendering of detail, based on close observation. Now artists became more concerned with immersing the viewer in atmospheric effects of light, shade and colour.

Many photographers were, in turn, inspired by artists to push technical boundaries and experiment with lenses, exposures, chemical treatments etc.

I see photography in this period as essentially another form of printmaking. A couple of engravings from steel plates feature in the exhibition, demonstrating that traditional printmakers still had an important part to play in the creation, reproduction and dissemination of art.

Ultimately, this show goes to prove that whatever the chosen means of expression, art advances through the imagination and talent of the artist, and their impact on the viewer.

The Cult of Byron

July 12, 2016

I spied this lithograph of George Gordon Byron (1788-1824) and his mistress Marianna Segati at a general antiques fair recently.

Lord Byron and Marianna. Lithograph with original colour by hand, by an unidentified printmaker. Possibly after William Drummond (fl. 1800-1850). [London: n.d., c.1840.]

Of course, as much as his words, the iconography of Byron shaped both perceptions in his lifetime and his legacy after his premature death of fever in Missolonghi in 1824. Famous in his lifetime after the publication of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812), and increasingly notorious when the scathing satire Don Juan (1819-24) appeared, he became an instant legend when he gave his life in the cause of liberation (of Greece).

Printed images of Byron circulated widely during his lifetime, and increasingly throughout the European Continent after his death – portraits of Byron were probably more numerous in the middle of the 19th century than of any other individual, except perhaps Napoleon.

Thomas Phillips‘ two portraits were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1814 and caused a sensation. His Byron in exotic Albanian dress in 1814 was of particular appeal to popular Romantic sentiment and spawned a glut of engravings after the original passed to Byron’s daughter, Ada, in 1835.

Byron by Thomas Phillips, oil on canvas, 1813 [NPG 142]

I find the portrayal of the sitters in my print rather revealing, and helpful when it comes to putting a date on it. Not intended for fine art lovers, this is barely a portrait at all, in the truest sense of the word. The black hair, curly and slightly wild, the big collar, are really mere signifiers: these were the characteristics the contemporary viewer expected to see in a Romantic poet, especially in Byron. Segati is allowed almost zero personality. The full, round faces are imbued with an early expression of the sentimentality that would come to characterize much Victorian popular art. Both protagonists are almost infantilized. Tenderness and affection are emphasized, and any hint of sexual desire relegated. This is a watered-down, family-friendly Byron.

This lithograph, published I would guess in the first few years of Victoria’s reign, seems to me to reflect the ambivalence towards the legacy of this reckless libertine in the face of a new morality. Heroes of the Victorian age were Christian and of upright character, and ultimately they were team players. For many years Byron’s individuality and uncompromising commitment to personal liberty sat rather uncomfortably with the official culture. That in part explains why it took until 1969 for the Byron memorial to be dedicated in Westminster Abbey.

My print is for sale as part of my Stock Showcase here: Byron and Marianna

The Wonder of Wisdens

May 25, 2016

It is rather remarkable when you think about it that the 153rd edition of the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack was published last month by Bloomsbury.

The ‘cricketer’s bible’ started life as an 116-page pamphlet produced by retired bowler John Wisden (known as ‘The Little Wonder’ due to his short stature), to promote his sporting goods and tobacco business. (The link between sports, advertising and the wicked weed goes back a long time.) If he knew that the little yellow book bearing his name was still being published – in basically the same format, though rather chunkier – a century and a half later he’d be bowled over.

And what would he make of an auction price of £8,400 achieved in recent years for one of those first 1864 Wisdens (cover price: one shilling)?

Most ventures into sporting annuals last a few editions and die – the periodical published by Wisden’s principal commercial rivals, the Lillywhite family, did not make it beyond 1900.

An 1864 First Edition, from Wisdens.org

Wisden has overseen the boom times and the lean years for the summer game with an independent eye. The fluctuating number of pages reflect the fluctuating appetites of the sporting public, the national mood and economic fortunes.

The suspension of First Class cricket during the years of World War I meant that the Almanack for 1916 could report only on school cricket – but crucially Wisden stayed alive. At 229 pages it is the slimmest edition since 1882 (the 2016 Wisden comes in at 1,552 pages).

Many of them are given over to reporting death. Greats of the game W.G. Grace, A.E. Stoddart and the Australian batsman Victor Trumper were not killed in the service of their King and Country. But a long alphabetical list of young men that follows, schoolboy and university cricketers, bears tragic witness to the first full year of conflict in 1915.

A 1916 Wisden (53rd Edition)

One name that leaps from the page is Sub-Lieutenant Rupert C. Brooke (Royal Naval Division). His six-line notice records a leading bowling average of 14.05 for the Rugby School XI and concludes with the famously pithy sentence: “He had gained considerable reputation as a poet”.

The precise intentions of the Editor, Sydney H. Pardon, are debated by Wisden historians.

My listing of Cricketana – including a very rare 1916 Wisden – can be viewed here: Cricket 2016

Georgian satire: the shock of the old

April 4, 2016

Since last month’s post inspired by my caricature of Mary Anne Clarke (see Mrs Clarke in the House) several readers have asked me about collecting satirical prints.

James Gillray’s The Plumb-pudding in danger, Pitt and Napoleon carving up the globe. Sold for £15,000 at Bloomsbury in June 2015.

Well it so happens I have penned an article on just that subject for a special supplement to the Antiques Trade Gazette (cover date 26th March 2016)

The early 1780s witnessed a new phenomenon, the professional caricaturist. And it was a uniquely British phenomenon. Only in Britain were the three conditions – freedom of expression, party politics, and a receptive market – combined.

Read my article on the Georgian heyday of the single-sheet satire here: Georgian satire: the shock of the old

There is plenty to interest the bibliophile in the newly-published supplement. It can be read online in full here: Books, Maps & Prints

Mrs Clarke in the House

March 18, 2016

Introducing Mary Anne Clarke (c.1776-1852), society hostess and royal mistress.

Mrs, M.A. Clarke. Hand-coloured etching by Charles Williams. London: S.W. Fores, February 1809

She pauses in front of the doors to the House of Commons, lifting her veil from her face and turning directly to the viewer, the hint of a knowing smile playing across her lips. By her side she holds a huge fur muff, the hand-warmer of choice of the fashion-conscious lady.

The elegant, alluring, and assured woman betrays no lack of confidence as she prepares to be cross-examined inside the Chamber for her role in a royal scandal surrounding the second son of King George III.

Clarke was the mistress of Frederick, Duke of York between 1803 and 1806. The Duke was forced to resign as Commander-in-Chief of the army in March 1809 after claims in Parliament that Clarke had received money in return for obtaining promotions. It seems she added names to lists which the Duke signed off, apparently not reading them very closely. Renounced by HRH, Clarke threatened to publish revealing memoirs and was able to extract huge pensions from the government to keep them suppressed. She proved herself an astute political operator.

The proceedings were, naturally, lapped up by caricaturists like Charles Williams (fl. 1796-1830), who swiftly etched this plate for sale on the 25th February 1809. Williams was a professional etcher of satires for London publishers about whom almost nothing is known. Like most satirical printmakers of his time, he favoured the etching technique as a fast medium capable of responding to the latest events within days. His more illustrious contemporary Thomas Rowlandson issued more than thirty satires on the Clarke affair, predominantly using etching.

Stipple portrait of Mary Anne Clarke from the ‘Lady’s Monthly Museum’ (1809)

Though a very simple composition – one of only a handful of caricatures in which Clarke is the sole or central figure – I find the image intriguing. Why did Williams present Clarke in this ‘attitude’ (in the artistic sense of the word)?

Some women who broke the mould and entered the public or political realm attracted the antipathy of the (overwhelmingly male) journalists, pamphleteers and cartoonists. And it is difficult, I think, to conclude that the characterisation of Clarke here is sympathetic. Rather is male chauvinism at play – Clarke as a symbol of the brazen woman of questionable virtue, enjoying her time in the limelight a little too much?

I’m certain Williams is pandering to the sense of novelty and mild titillation engendered by a self-confident, attractive young woman strolling into the heart of the political Establishment, effectively to give evidence against a senior royal. There is an undeniably journalistic feel to the image: Clarke poses like a latter-day red carpet celebrity for the paparazzi.

To no one’s surprise, the Duke was cleared of any personal wrongdoing and was reinstated to his command in 1811. As for Clarke – after conviction for libel over one indiscreet publication too many and jail time in 1813 – she moved first to Brussels, then to Paris. She died at Boulogne in 1852. Her life inspired a novel, Mary Anne, by her descendant Daphne Du Maurier.

The caricature by Charles Williams is available for sale: http://jenningsprints.tumblr.com/post/135311403528/the-scandalous-woman-who-took-on-the-british

Something Fishy in Revolutionary New York

February 9, 2016

It’s often said that we humans see what we want to see, and particularly it seems when directed by an artwork’s title or caption.

The subliminal power of text to influence the way we look at an image always amazes me – it’s something I’m very aware of when I’m buying prints. It is all too easy to uncritically accept the identification of a sitter or location, or the attribution to an artist.

L’Arrive du Prince Ouillaume Henry a Nouvelle York. Etching with contemporary hand colouring by Balthasar Friedrich Leizel or Leizelt. Augsburg, Germany, c.1782.

I must confess when I first set eyes on this print I was guilty of reading the legend a little unquestioningly. The engraved lettering above and below the marine composition (in both French and German) proclaims the arrival of the ship carrying a young Prince William Henry, the future King William IV, into New York on the 16th October 1781.

Read the rest of Jasper’s article on the interplay of original art and print across international borders here: ARTICLE for the January 2016 ABA Newsletter (PDF)